In South Korea, remembering Rabindranath Tagore, for inspiring a generation of freedom fighters

Some 4,000 km from undivided Bengal, where he was born, a bust of Rabindranath Tagore stands on a busy street in Seoul’s Jongno district, near Marronnier Park, silently observing scores of passersby. It was erected in 2011 in a university neighbourhood by the South Korean government to commemorate the Nobel laureate’s 150th birth anniversary, in coordination with the Indian embassy.

Around the world, particularly in countries where Tagore travelled—from the US to Japan—it is not uncommon to find statues and plaques commemorating one of South Asia’s most prominent literary and political figures. But the memorial to Tagore in South Korea is unique.

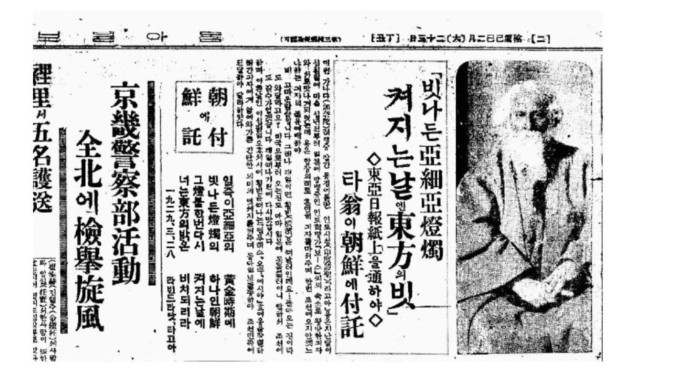

A copy of the edition of the Korean newspaper Dong-A-Ilbo published on April 2, 1929, featuring Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Lamp of the East’ translated by Chu Yu-han into Korean. (Photo credit: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

A copy of the edition of the Korean newspaper Dong-A-Ilbo published on April 2, 1929, featuring Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Lamp of the East’ translated by Chu Yu-han into Korean. (Photo credit: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

This is because although Tagore never visited the Korean Peninsula, his work left a deep impact on people in Korea during their fight for freedom from Japanese colonisation.

While Tagore did not reach Korea’s shores during his lifetime, he did travel to neighbouring China and Japan between 1916-1924. It was during this time that Tagore got an opportunity to understand the socio-politics that were unfolding. These were very different from the perceptions that he had formed while back in his homeland.

“When Tagore visited Japan for the first time in 1916, he was disappointed to see that Japan was imitating the ways of the imperialist West. His indictment of Japan on the path of war cost him ovation and affection with which he was initially greeted,” says Dr Pankaj Mohan, one of India’s leading experts on the colonial history of Korea and Korea-India relations.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by GRΛNΛDΛ (@granada_k_official)

That Tagore never visited Korea was not for the paucity of invitations. Sometime during the 20th century, Korean intellectuals discovered his works in translation. “In the early 1920s, about 250 of Tagore’s works were introduced. And in the history of Korean translated literature before Independence, there is no example of so many works by a foreign poet being translated,” says Professor Kim Woo Joo, who teaches Hindi literature at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul. He obtained his Ph D from Visva Bharati University in Bolpur, West Bengal.

While Tagore knew little about the extent of Japan’s brutal colonial practices and heaped praise on the Empire in what was called pan-Asian solidarity, Korean intellectuals who looked up to him as an anti-colonial figure very much knew of Tagore’s opinions on Japan and tried to inform him about their lived realities.

It was in Japan that Tagore first met Koreans who had been living under Japanese imperial rule. And this truly shaped his opinions on the empire’s colonial policies. Japan’s colonisation of the Korean Peninsula from 1910-1945 was brutal. While imperialist policies meant the imposition of several rules and curbs on freedoms and the human rights of Koreans, there were also other forms of violence.

Approximately 1,50,000 Koreans were forced to work in factories and mines in Japan during the Second World War. Thousands of Korean girls and women were also forced into sexual slavery in military brothels. These historical occurrences have remained points of contention between Japan and South Korea since both countries formally established diplomatic relations in 1965.

Dr Mohan points to the writings of Charles Freer Andrews, an English Anglican priest and social reformer who also worked for the cause of Indian independence and was a close friend of both Mahatma Gandhi and Tagore.

“Charles F. Andrews, who accompanied the poet to Japan, noted: ‘When (Tagore) spoke out strongly against the militant imperialism which he saw on every side in Japan and set forward in contrast his ideal picture of the true meeting of East and West, with its vista of world brotherhood, the hint went abroad that such ‘pacifist’ teaching was a danger in war time and that the Indian poet represented a defeated nation’,” Dr Mohan says.

K-pop group ‘Granada’, performs a fusion of Rabindra Sangeet with Korean traditional musical instruments at a commemorative event jointly held by the Embassy of India along with the Embassy of Bangladesh in honor of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth anniversary at Nami Island, South Korea in May 2024. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

K-pop group ‘Granada’, performs a fusion of Rabindra Sangeet with Korean traditional musical instruments at a commemorative event jointly held by the Embassy of India along with the Embassy of Bangladesh in honor of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth anniversary at Nami Island, South Korea in May 2024. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

The Song of the Defeated

When the Japanese realised that Tagore was becoming more critical of Japan’s imperialist policies in the Korean Peninsula, their sentiments towards the laureate began to change. Andrews states that accusations of Japanese critics that Tagore preached the sermon of peace because he was poet of the “defeated country” inspired Tagore to write the poem entitled The Song of the Defeated. This would go on to become an iconic poem associated with Tagore with immense relevance in the study of colonial Korea.

This poem reads:

“She is silent with eyes downcast; she has left her home behind her.

From her home has come wailing in the wind.

But the stars are singing the love-song of the eternal to a face sweet with shame and suffering.”

“Tagore gave this poem to a Korean student in Japan named Chin Hakmun, who visited him at the Yokohama residence of Hara Tomaitaro (in July) 1916 and requested him to contribute either an essay or verse to the Korean journal “Cheongchun” or Youth. By giving the poem to a Korean student, the poet wished to underscore the common destiny of India and Korea, and to boost the sinking morale of the Korean people, yoked to the repressive colonial rule of Japan,” says Dr Mohan.

One of the first invitations to Tagore to visit Korea came in 1916 through young Korean students whom he met while in Japan. Unable to travel to the peninsula, Tagore instead shared a poem with a young Korean writer. That poem came to be known as The Song of the Defeated.

“I think he recognised Korea as ‘the defeated’ country just like his native India. This poem can be interpreted in multiple ways, and one of them is that it can be understood as a poem describing the longing to meet the lost homeland,” explains Professor Kim.

The Song of the Defeated is not a poem written separately for the Korean people under the Japanese colonial rule, but is the 85th poem included in Fruit Gathering, a collection published in 1916.

A photo from a commemorative event jointly held by the Embassy of India along with the Embassy of Bangladesh in honor of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth anniversary at Nami Island, South Korea in May 2024. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

A photo from a commemorative event jointly held by the Embassy of India along with the Embassy of Bangladesh in honor of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth anniversary at Nami Island, South Korea in May 2024. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

Professor Kim says, “Poems of this collection were translated from Bengali into English by Tagore and it can be assumed that Tagore gave it to a young Korean writer because he considered it to be the most appropriate among the published translated poems, considering the situation Korea faced.”

While they were not specifically written for the Korean people, researchers believe that one of the reasons why some of Tagore’s poems resonated with the Korean people living under Japanese colonial rule was that they exhibited his empathy towards others suffering from the violence and brutality of colonial rule. However, some historians believe that for many anti-colonial Koreans, what made Tagore stand apart from his contemporaries who were also writing about colonial oppression was that unlike them, he had openly expressed his criticism to the Japanese.

“Stephen H. Hay in his book Asian Ideas of East and West: Tagore and His Critics in Japan, China, and India tells us on the evidence of his 1955 interviews with key figures associated with Tagore during his 1916 sojourn in Japan…that several Korean students visited his residence at Yokohama and also talked to him at campuses of Japanese universities where he was invited to deliver lectures. It was indeed through these private conversations that Tagore was awakened to the harsh reality of Japanese imperialism. He was deeply aggrieved to learn about the atrocities Japan perpetrated on Korea which it had annexed six years earlier,” says Dr Mohan.

It was not that people in the Indian subcontinent were completely unaware of Japan’s colonial brutality. Archival documentation indicates that the nationalist press, run by revolutionaries and freedom fighters, had been highlighting the colonisation of Korea and the fight for freedom by the Koreans. But perhaps there was a lack of sufficient knowledge about the extent of the violence that was being perpetrated on the Koreans. It took in-person interactions with Koreans for Indian freedom fighters and revolutionaries to understand the shared grief and resistance of both peoples.

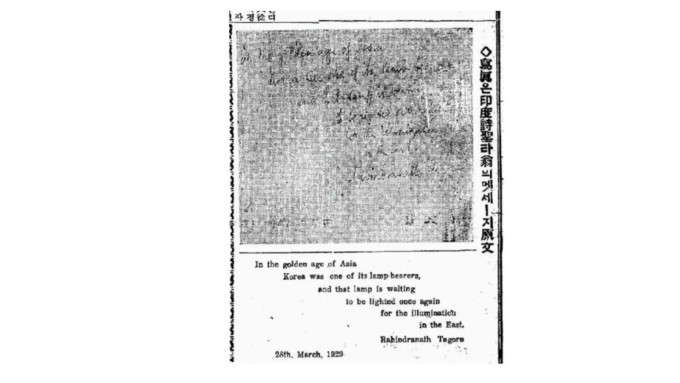

A copy of the edition of the Korean newspaper Dong-A-Ilbo published on April 3, 1929, featuring Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Lamp of the East’ in its original English version. (Photo credit: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

A copy of the edition of the Korean newspaper Dong-A-Ilbo published on April 3, 1929, featuring Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Lamp of the East’ in its original English version. (Photo credit: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

Freedom fighters not entirely uncritical of Japan

While it is true that during their own quest for freedom from British rule, many freedom fighters and revolutionaries looked up to Japan for inspiration, it would be doing a disservice to their contributions to believe that they were entirely uncritical of Japan’s imperialist and colonial policies, scholars told indianexpress.com.

Till the early 1900s, Indians at the forefront of the freedom struggle, like Tagore and Gandhi, harboured romantic views of Japan, but they were also astute and perceptive enough to analyse and criticise Japan’s policies.

It was not that Tagore believed Japan was the “leader” of Asia, a label that is sometimes inaccurately ascribed to him. “He believed that great Asian powers such as India and China were reduced to the status of colonies or semi-colonies respectively, but Japan maintained its independence. So Japan needed to ‘fulfil its mission of the East’ and to ‘infuse the sap of full humanity into the heart of modern civilisation’,” says Dr Mohan.

On Tagore’s last visit to Japan in 1929, another invitation to visit Korea came, this time from Seol Eui-sik, the Tokyo correspondent of Dong-A Daily, a Korean newspaper. Seol invited (Tagore) to visit Korea as the guest of his paper, and also requested him to write a few words to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the March First Independence Movement, arguably the most powerful symbol of Korea’s will to gain independence and the greatest expression of anti-imperialist protest in the colonial history of Korea, says Dr Mohan. “Tagore obliged him by composing the famous quatrain,” he adds.

“That poem later went on to be named as Lamp of the East and only recently, during research by Korean scholar Dr Kim Jae-young, was Seol identified as the Korean journalist whom Tagore met in Japan,” Dr Mohan says.

During this visit to Japan, Tagore also agreed to finally visit the land that he had inspired so deeply through his words. However, the development of a heart ailment while in Japan compelled him to put a stop to his travel to Korea.

Tagore would go on to write about his interactions with Seol in an essay which was originally published in a Bengali magazine titled Koriyar Yubaker Rahtrik Mat (Nationalist View of a Korean Youth), and later it was included in his book Russiar Chithi (Letters from Russia), as an appendix, according to Dr Mohan.

“When Tagore met Gandhi at Ahmedabad in January 1930, they discussed a range of topics, but it is remarkable that on this occasion the poet also shared with Gandhi the views about national independence that he had exchanged with a Korean youth in Japan the previous year,” Dr Mohan says.

The remarkable conversation that Gandhi and Tagore had about Koreans and their fight for freedom from Japanese was documented by Madhav Desai, Gandhi’s personal secretary and exists in archival records.

Tagore poem in Korean school textbooks

Today, Korean middle school textbooks feature Tagore’s poem Lamp of the East. One reason for the inclusion of this poem in the official curriculum is its use during commemorations for the March First Movement or the Independence Movement Day in South Korea, pronounced Sam Il Jeol, a national holiday in remembrance of people who spearheaded Korea’s independence movement and liberation from Japanese colonial rule.

Instrumental in taking the voices of Indian independence leaders to the Korean people were the newspapers Chosun Ilbo and Donga Ilbo, which remain in publication in South Korea today. Founded in 1920, these newspapers would regularly carry articles about Gandhi and Tagore, using Indian independence leaders living in exile overseas in East Asia as their sources for information.

This national holiday is important in South Korea. Dr Mohan says, “Tagore’s poem that commemorated and eulogised the March First spirit was often quoted as an evidence of the international influence of the March First Movement. It was, perhaps, against this background that the poem was included in middle school textbooks.”

When Tagore sent his four-line poem as a message to the Korean people in 1929, he sent it without a title. “The Lamp of the East is a short ode reflecting Tagore’s views on the East at the time, but he wrote it himself and sent it to Korea,” says Kim.

This short poem is also inscribed on a plaque beneath Tagore’s statue in Seoul today:

“In the golden age of Asia,

Korea was one of its lamp-bearers

And that lamp is waiting to be lighted once again

For the illumination in the East.”

“The message that Korea would shine in the East gave great comfort, encouragement and hope to the Korean people who were suffering during the dark times of cruel and severe Japanese colonial rule around the 1930s,” says Kim. When the poem reached Korea, it took on the title it is now known by, The Lamp of the East.

The reason why Tagore’s connection with colonial Korea does not get enough attention may have to do with the quantity of his writing on the country.

A bust of Rabindranath Tagore which was established in Jongno district, Seoul, South Korea in 2011. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

A bust of Rabindranath Tagore which was established in Jongno district, Seoul, South Korea in 2011. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

“Tagore wrote only one poem and one article on Korea, but in contrast he composed many essays and poems on China and Japan. He also directly interacted with and influenced a large number of Japanese and Chinese scholars, literary figures, artists and politicians. This is also evident in Jorasanko Thakurbari Museum in Kolkata, where one sees several rooms dedicated to Tagore’s connections with China and Japan. It is natural, therefore, that a large number of books and research papers deal with the topic of Tagore’s view of China and Japan and his influence on the Chinese and Japanese minds,” says Dr Mohan.

But that is changing now, with more scholars, particularly those in East Asia, investigating Tagore’s bonds with colonial Korean and its people.

‘Young Koreans interested in India but…’

Despite his poem being taught in middle school, whether ordinary Koreans would immediately recognise Tagore and his work depends on whom one asks. “I think that ordinary Koreans don’t know much about Tagore. But Koreans above age 60 know that Tagore was a poet and the first Asian to win a Nobel prize with Gitanjali,” says Prof Ha Jinhee, an expert on Korea-India relations, formerly at Jeju National University.

“Young Koreans are very interested in India; they travel for tourism and they like Indian food. But sadly they are not interested in Indian culture and literature. We are educated and focused on western culture even though (India and South Korea) are under the same umbrella of Asia,” says Prof Ha.

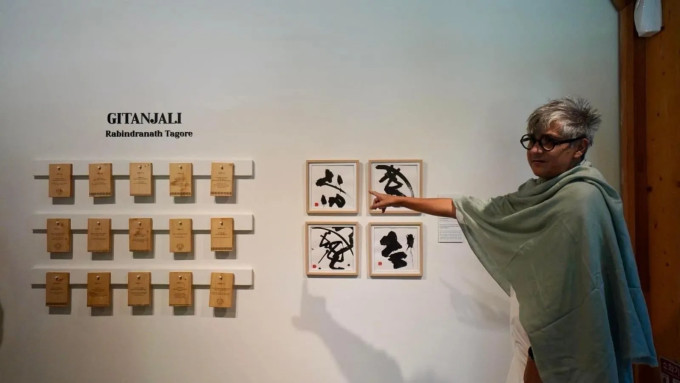

On May 3, at Nami Island in South Korea, the embassies of India and Bangladesh jointly commemorated Tagore’s 163rd birth anniversary. In addition to performances by Indian, Bangladeshi and Korean artistes, K-pop group ‘Granada’ performed a fusion of Rabindra Sangeet with Korean traditional musical instruments.

India’s Ambassador Amit Kumar at a commemorative event jointly held by the Embassy of India along with the Embassy of Bangladesh in honor of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth anniversary at Nami Island, South Korea in May 2024. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

India’s Ambassador Amit Kumar at a commemorative event jointly held by the Embassy of India along with the Embassy of Bangladesh in honor of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth anniversary at Nami Island, South Korea in May 2024. (Photo credit: Embassy of India, South Korea)

“Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore…made seminal contributions to arts, music, and literature and was the first Asian to win the Nobel prize in 1913. His literary works, particularly poems, were closely followed in Korea,” Amit Kumar, India’s ambassador to South Korea, said during the commemoration at Nami Island.

“I remember very well when the Tagore statue was erected. Originally, it was going to be built at Gangnam Station, but the plan was postponed. Then Kim Yang-sik, director of the Indian Art Museum, connected with the Jongno-gu office and erected the bust in Daehak-ro, Hyehwa-dong, where many college students go. I offered flowers to the statue (back then). Now, the Indian ambassador and the Indian Cultural Center are leading the way. This time, for the 163rd anniversary of Tagore’s birth, several people have planned to recite Gitanjali together,” says Korean poet and author Chae In-sook, vice-chairman of the Korean Literary Association’s Recitation Committee.

Tagore and his relevance in Korean history and for the Korean people is evident in the very fact that a statue of the Nobel laureate exists even in a country that he did not visit. “The statue of Tagore on Daehakro, also known as University Street, is one of Seoul’s cultural centres. It is very rare to have a statue of a foreign writer in South Korea,” says Prof Kim.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.