‘How long must I keep this 24/7 vigil?’: In the wake of Kolkata’s RG Kar rape-murder, 7 doctors share experiences with ‘safety’ at hospitals

India marked 78 years of independence on August 15. The mood of the nation, however, was anything but celebratory. There was, and still is, widespread angst and anger over the horrific rape and murder of a woman trainee doctor at the state-run RG Kar Hospital in Kolkata.

On August 14 at midnight, thousands of women, and many men, marched through the streets of Kolkata and other parts of West Bengal in protest. Dubbed India’s biggest “Reclaim the Night march,” the widespread protest was reminiscent of the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 70s. Their demand? Safety—a right promised by the Constitution of India.

Doctors across the country went on strike demanding safety at workplaces, but recently agreed to resume duties after the intervention of the Supreme Court. In this context, we spoke with seven doctors––at different stages of their careers and from various parts of the country––to understand what “safety” has meant to them over the years.

Doctors protest over the RG Kar rape and murder case. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Doctors protest over the RG Kar rape and murder case. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Dr Manas Kamakshi Sharma, 24, MBBS intern

“If you ask a doctor about safety in government hospitals, they’ll laugh at you. There’s hardly any security for patients, doctors ki toh dur ki baat hai (it’s even worse for doctors),” says Manas, 24, a queer intern at a private hospital in Gurgaon.

Working in a highly-gendered space, Manas recounts feeling unsafe both physically and emotionally due to inadequate support and understanding from the administration. Despite working in a private hospital, there are no separate duty rooms for male and female doctors on night shifts.

“When we’re on night shifts, all of us have to use the same room. Many of my women colleagues, and I myself, have felt unsafe sleeping in these rooms since anyone can come and go. So we end up staying up all night,” Manas said.

The lack of policies protecting LGBTQ+ doctors has further exacerbated this sense of vulnerability. “I wish we have clear anti-discrimination policies and inclusivity training. We need a safety and protection act to ensure our well-being at the workplace. As doctors, we spend nearly half our lives at work. How long can we maintain constant vigilance without compromising our health and safety? Do we give up on sleep? Should we constantly be on the lookout? When does it end?” Manas had many questions.

Central Industrial Security Force (CISF) personnel stands guard at the entrance of R G Kar Medical College and Hospital (Source: Reuters)

Central Industrial Security Force (CISF) personnel stands guard at the entrance of R G Kar Medical College and Hospital (Source: Reuters)

Devya, 21, MBBS student in her second year

The 21-year-old aspiring doctor, Devya, is apprehensive about starting night shifts. “I’ve heard stories from my seniors about patients claiming an ‘altered sensorium’ and trying to touch female doctors inappropriately.”

She said that many of her senior colleagues avoid going out for chai during night shifts due to safety concerns from local miscreants. Devya hopes for increased CCTV coverage at her hospital in Assam to improve security.

Dr Gunjan Arora, 25, consultant physiotherapist

Gunjan, 25, has never used the restroom or changing room during emergency night shifts at her hospital. “There are no female guards on duty at night, let alone a separate changing room,” she said.

Some of the other hospitals she worked with during her internship in Haryana also lacked separate changing rooms and rest areas for female doctors and nurses. “If this issue ever came up, the administration would just say, ‘We will ask men not to come to that area’,” said Gunjan. “Safety is simply a basic right for every human being. But most of the hospitals fail in providing even that,” she said.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by The Indian Express (@indianexpress)

Dr Himanshi Jindal, 32, junior paediatric consultant

“Many times” Himanshi, 32, said, when asked if she’s ever felt unsafe at a hospital she’s worked in. “Almost all of my women colleagues would have something similar to say,” she said.

She recalls hiding from a deceased patient’s angry relatives for hours. “There were 20-30 of them searching for me. I had to hide for four hours in a room to avoid them. They were really angry, and my head of the department had to intervene. I was so scared,” said the paediatrician, now working in Mumbai.

During her internships in Maharashtra, she rarely encountered safety measures for doctors. For instance, she once had to transfer a critically-ill child alone in an ambulance with two male relatives, making her request her brother to follow the ambulance. She also said that night shift doctors were often confined to a small, inadequately-equipped room. “A barely-functioning table fan, and one bed for three people on duty,” she said.

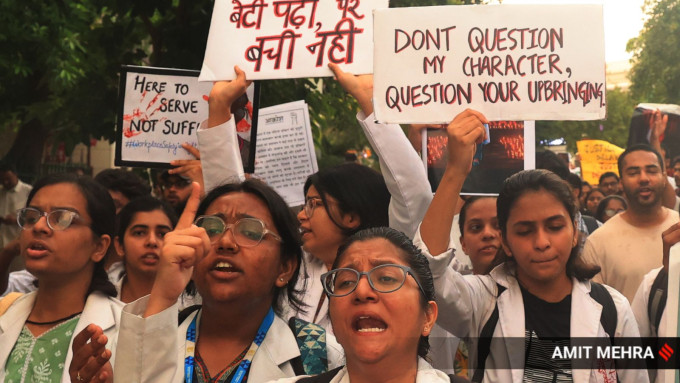

Members of various Resident Doctors Associations protest during a candle march against the alleged rape and murder of a woman doctor at Kolkatas RG Kar Medical College and Hospital at Connaught Place. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra)

Members of various Resident Doctors Associations protest during a candle march against the alleged rape and murder of a woman doctor at Kolkatas RG Kar Medical College and Hospital at Connaught Place. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra)

Dr Dipshikha Ghosh, 35, critical care medicine

Dipshikha, 35, sheds light on the pervasive sexism in medicine, especially towards women doctors. She recounts being harassed during her MBBS years, including a disturbing incident where someone photoshopped her face onto a nude body and circulated it with personal details and “rate”. When she reported it, the college downplayed the incident, citing concerns of the perpetrator taking his own life if they pursue the issue. “Women are often told, ‘You are overreacting, maybe he didn’t mean it like that’,” said Dipshikha.

She said she knows many women doctors who left their jobs due to harassment, including sexual misconduct from colleagues or seniors. In her early days working in rural West Bengal, she said, “There was no security at night. We had to protect ourselves on our own from drunk, abusive, violent patients in the night when nurses wouldn’t be present in the OPD area or in the Emergency room and the Medical Officer on duty would have retired for the night to sleep.”

While her current hospital in Kolkata provides better security measures, including key-card access, CCTV, and guards, she still feels uneasy. “For instance, I will be waiting for an elevator and it opens to six to eight men inside. Maybe nothing will happen, but I can’t risk it. Even with the amount of security and cameras there are. Because, if something happens, I know people will lead with ‘Why did you walk in when you saw so many men? You should have known better’,” she said.

RG Kar College and Hospital junior doctors paint a graffiti during a protest (PTI Photo)

RG Kar College and Hospital junior doctors paint a graffiti during a protest (PTI Photo)

Dr Namitha Mary, 26, PG aspirant

Namitha, 26, recounts a troubling experience during her house surgeoncy in Kerala, where she and a small team had to fend off a group of drunk men demanding treatment at midnight. “They were very drunk and were catcalling us and talking inappropriately. It was with much difficulty that the nurse sent them back. Even if they had done something, there wouldn’t have been anybody to help us. The irony is this is not a single incident. It is one of many,” she said.

Many of her peers have faced similar or worse situations. For example, a colleague once woke up to find a stranger in their unsecured duty room. This had come right after Dr Vandana Das, a 23-year-old doctor in Kerala was stabbed to death by a patient.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by The Indian Express (@indianexpress)

“We work 24-35 hours, even more, without rest, and the least we can expect is a safe working environment. Most often, our safety is taken for granted but there is a chance of attack every single hour; be it from patients, bystanders or even complete strangers. The basic right of everybody is a safe working environment so why are doctors being denied that?” said Namitha.

Dr Yasmin Imdad, 47, senior consultant obstetrics & gynaecologist, Kinder Hospitals, Bengaluru

Yasmin decided to work at Kinder Hospitals in Bengaluru for a very specific reason. “Driving alone at night, particularly on empty roads, scares me. I chose my current workplace because of its proximity to my home, which is just five minutes away. This closeness allows me to reach the hospital quickly, even during late-night emergencies. It adds a sense of security to my routine,” she said.

Despite this, she prays for safety each time she leaves for a night shift. Yasmin also recalled the lack of safety measures during medical school and postgraduate training in government colleges. As a senior doctor, Yasmin believes it’s essential to have secure duty rooms with keycard or biometric access, CCTV monitoring, panic buttons, and mobile SOS apps.

Protests continue at RG Kar Medical College and Hospital. (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

Protests continue at RG Kar Medical College and Hospital. (Express Photo by Partha Paul)

“Pairing junior doctors with experienced seniors can foster a supportive environment where they work together as a team, particularly during night shifts. Implementing a buddy system ensures that no doctor is working alone, thus enhancing their safety,” said Yasmin.

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.